How can a place with the scale and inaccessibility of the tar sands be made sense of? Suddenly a toxic shape expands in the landscape after company leases are negotiated well away from due public process. Photographs from planes make for spectacular images, but at ground level, where we live, trees, habitats, aquifers, and rivers are poisoned, and criss-crossed by leaking pipelines.

I enter the HQ of this oil company. It has taken a year to find a way through the fortress wall of an oil company to find access into one of the many in situ, live-in camps for shift workers. Having learned portraiture as a way to share time with shift workers, I’m aware that a portrait artist can pass under the radar to access workers in a way that a researcher or journalists may not.

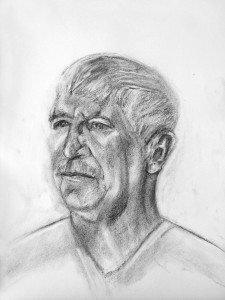

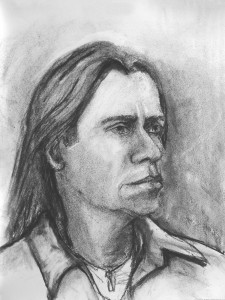

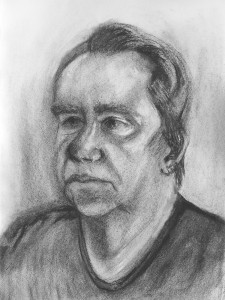

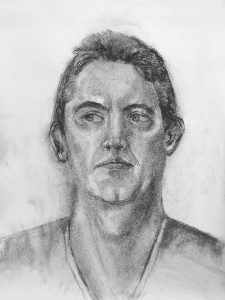

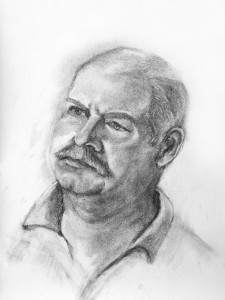

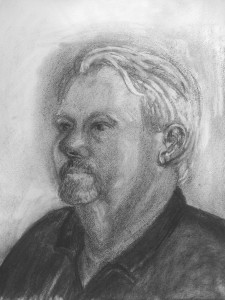

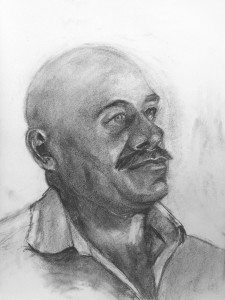

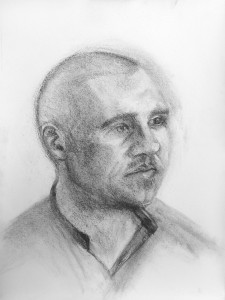

Most of the 24 people I drew needed to talk, needed to tell me a lot about themselves, needed to articulate their pasts, present or futures, sometimes with great intensity. Observing is about seeing subtlety, finding where it is light and where it is dark. The process moves you inward, expands and contracts time while unfolding a unifying space between the observer and observed. In this 24/7 transitory environment, relationships to labour, the environment, and to one’s self can be tenuous. Being drawn encourages being listened to, being seen, and being felt, which is the antithesis of how people find themselves in this work environment.

People say there are not enough oooo’s in smooth to describe this onsite manager who gives tours to VIP guests who want to come see the largest oil project in the world. While we drive he gives me the good news story, like a recording that goes on then off with no trace of personal ownership. He is a practiced Pentecostal minister and delivering a message is something he can do. We drive in to the beginning of the extraction area, where up to 40 000 workers live transiently.

Artefacts, things that could hold and link us to our past, dating back thousands of years, are at rest with their stories in the earth, until the soil and all the life growing from it was declared overburden to the oil below. Day and night the diggers claw away at the identity of this vast space leaving a raped and haunted landscape behind.

I set up two chairs in the corner of the camp foyer, non-stop pop music is playing in this space of a security desk, a doughnut and coffee counter, rarely used seating arrangements, vending machines and workers checking in or out with their bags. The adrenalin-fuelled person in use through long hours of work here masks a more fragile one that our capsule of drawing space encourages into visibility.

Human beings are transformed into vehicle bodies with solitary heads seen at their windows. They crisscross a landscape devoid of plant and animal life, moving through mechanically and chemically separated earth layers, passing toxic ponds and sulphur mountains, and breaking shortly before the next 12-hour shift begins.

A smiling woman who is wearing an identity badge that says “First Impressions Manager” greets me. She shows us around the camp that sleeps up to 3000 and whose design is borrowed from a prison. The first camp activity room we visit is a cards room where each year poker winners are sent to Las Vegas to play for bigger stakes. Outside there is a racing track for miniature battery operated vehicles and an overgrown sports court. I suggested planting vegetables as she was a gardener, but she said everything is poisoned up here and you would not plant, fish, swim, or forage anywhere. I ask her “did anyone ever ask you about second impressions?”

An absence of value permeates through everything in this barren zone, and comes right to our front doors. Nobody belongs here now. Each job carried out by each person amounts to removing something and taking more memory, life, and health out of the landscape. Few people working in this giant mine will wonder about what was here before; this is not useful. It is best to shut down, shut off, be used by the system, and hope the future price of waking up is not too high.

Man from Quebec: “This is not a place, it’s all sex drugs and alcohol, it’s not worth it. The guys who make 2000 dollars a week and have nothing left by Monday will be here another 30 years. You do not ask too many questions, you would not be here if you did. You have to be careful not to want bigger and better things, I work three days then three nights—I’m here for that.”

Most conversations here are about places, which are far from here. I am thinking about the denial of a place or of the history of a place. I come across a quote from Lucy Lippard. “For many displacement is the factor that defines a colonized or expropriated place. Even if we can locate ourselves we haven’t necessarily examined our place or our actual relationship to that place.” *

Chinese man from Edmonton: “At work there is terrible-back stabbing, I just keep my head down and don’t say anything. The stuff you see on site … you just have to carry on … there’s a lot of people you don’t like—you don’t say anything—carry on. The company screws you, my wife pushes, pushes too much—she wants an even bigger house now, she wants more and more.”

In the absence of a settled environment and relationships, notions of place swell in the minds of shift workers living in camps. A survival line gets cast to a place or idea of belonging and takes a form for each lonely person in this denuded landscape. There is little left to take in this torn up landscape accept for the large paycheques that keep generating more expenditure and less knowledge of where we are.

Lebanese man from Edmonton: “I have never sat still for this long. I do not like it, it makes me think.” Me: “… that you do not want to be here?” Him: “Yes” Me: “If you could go back in time would you have stayed in Lebanon?” Him: “Yes.”

Most shift workers spend more time living in camps than they do at home. At camp each private space has to be cleaned every other day, there is no choice; it is part of the wider security, keeping a check. Guards check the workers on their way into the kantine and then it’s an all you can eat buffet, comfort and surveillance.

Woman from Cape Breton: “I clean the camp rooms seven days on then I have seven off where I have nothing to do but hang around the camp, as flights home are too expensive. Most of the rooms I clean are disgusting with spit in the sink, sweaty clothes on the floor, flicked snot on the ceiling and walls. I am up and down like the other women my age here (+/- 50) but I find it hard to stop working, I’ve been working since I was 14.”

Self is a resource that also becomes exhausted, through lack of sleep, support, privacy, and connection to family, friends, and place. What is the cost of recovering a human?

Digger/operator from PEI off work after an aquifer was pierced: “I come from a very quiet place, very quiet parents. I hear the men in the adjacent rooms here. I hear them in the toilet. I have to speak to my girlfriend under the covers. It’s no good up here, relationships breakdown up here.”

Ground water routes are largely unmapped in Canada and contamination travels far from areas of excavation, fracking, or steam assisted drainage. Trying to stop high-pressure leaks from punctured aquifers can take years. Regulations for water used by the industry suit profit models, not the safety of drinking water hundreds of miles away.

BC man writing safety report: “I would not work on a fly in fly out site where people are exhausted and disoriented from the long flights from home and where more accidents happen. [Shows me pictures of toppled cranes.] In my first week I was sprayed by benzene coming out of a pipe and no one had bothered to report it. These very young engineers have little practical experience or sense of responsibility. I found open valves that had the potential to explode an area the size of several football fields.”

Acadian from cape Breton: “Companies keep you on with the promise of work even when they don’t have it or punish you if you quit. I refuse to be a foreman—this requires taking responsibility for all the workers when some are overworked, under-slept, on drugs. Some are assholes on the job because they know the union won’t fire them. There was a mentally unstable guy who disappeared and they found him hitching down a heavy hauler road.”

Each of the workers living in the camps are dealing with some kind of conflict in balancing the place or places where they come from with the long days or nights of shift work. Operations are so large here that jobs and money appear to be endless but the money comes at a big expense. Once arrived the worker is drawn into complex and anonymous patterns of shift work that can leave them feeling bereft of autonomy and sense of common purpose. Given that the oil companies only have one central goal it is hard to imagine there is ever going to be a genuine interest in enabling anything or anyone who gets in the way of their numbing, abusive, and hard-core drive for profit.